By Ross Exler

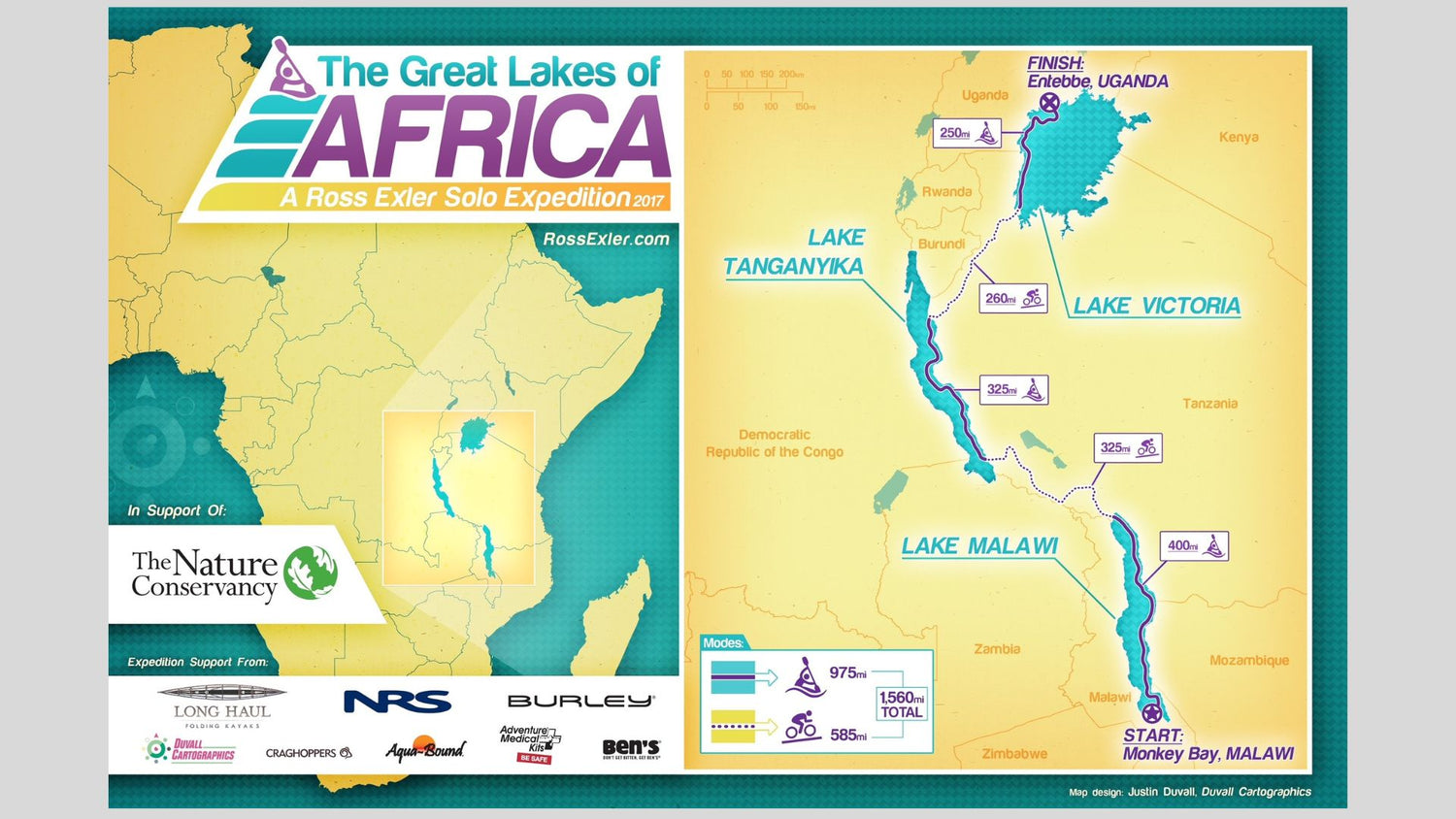

This January, adventurer, biologist, and photographer Ross Exler will embark on the first ever human-powered solo-crossing of the African Great Lakes system in support of The Nature Conservancy. His journey will include approximately 1,000 miles of paddling across the lakes with 600 miles of biking between the lakes and will take him through remote parts of Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Uganda. We’re excited to support Ross as he seeks to raise awareness about the lakes and support conservation efforts. Below, Ross shared with us about his decision to make this journey and his plans for safety. – Adventure Medical Kits

For many years now, I’ve been driven to go out and explore wild places around the world. In 2015, I paddled an inflatable kayak 1,000 kilometers through the Ecuadorian and Peruvian Amazon, staying each night in small villages. When I hit the Amazon River, I had a small motorized canoe built, which I navigated a couple thousand more kilometers through Peru, Colombia, and Brazil. To date, I’ve spent about 2 years of my life traveling in Africa, mostly solo expeditions, and have visited dozens of wilderness areas in East and Southern Africa.

My next expedition, which will commence in January 2018, will be the first entirely human-powered, solo-crossing of the African Great Lakes system. I will attempt to paddle a kayak across Lake Malawi, Lake Tanganyika, and Lake Victoria, traveling between the lakes via bicycle and along with all of my equipment. The journey will be over 1,600 miles and will take me through remote parts of Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Uganda. I’ll be doing the trip alone, and every mile will be earned through the fair means of paddling or bicycling.

When I tell people about this expedition, they usually ask me one of two questions:

- What are the African Great Lakes?

- How do you stay safe?

I find that first question to be rather tragic, serving as further motivation for my trip, while the second question certainly deserves considerable thought. I’ll try to briefly answer both.

What are the African Great Lakes?

I was first introduced to the African Great Lakes when I worked in a college lab studying several species of fish from Lake Tanganyika. I soon found out that these lakes have some amazing distinctions: Lake Tanganyika is the longest lake in the world, the second deepest (over 4,800 feet deep), and the second largest lake in the world by volume. Lake Victoria is the largest tropical lake in the world by surface area, and the second largest overall. Lake Malawi is the fourth largest freshwater lake in the world by volume. Altogether, the lakes comprise nearly 25% of the world’s unfrozen freshwater.

Further, the lakes are remarkably important for biodiversity. They contain thousands of species of fish, with as much as 10% of the world’s species of fish living in these three lakes alone. By some estimates, Lake Malawi holds the largest number of fish species of any lake in the world. Additionally, the shores of Lake Tanganyika include the Mahale Mountains and Gombe Stream, both known for their populations of chimpanzees.

Unfortunately, the lakes are under threat due to overfishing, invasive species, climate change, and pollution inputs from deforestation and other human activities. These impacts are all contributing to ecological degradation of the lakes. One estimate suggests that over 200 species of cichlids found only in Lake Victoria have gone extinct in the past 30 years alone. These environmental issues also endanger the millions of people who live along the shores of these vast lakes.

After having visited the African Great Lakes region and completing my solo Amazon expedition, I came up with the idea of enchaining the three largest of the African Great Lakes by kayak and bicycle. As I planned the expedition, one of my goals was to team up with a conservation non-profit who works within the region, to help increase awareness.

After having visited the African Great Lakes region and completing my solo Amazon expedition, I came up with the idea of enchaining the three largest of the African Great Lakes by kayak and bicycle. As I planned the expedition, one of my goals was to team up with a conservation non-profit who works within the region, to help increase awareness.

That’s when I came across the work of The Nature Conservancy’s Tuungane Project, which operates along the Tanzanian section of Lake Tanganyika. The Tuungane Project brings a multidisciplinary approach to conservation and addressing the extreme poverty that is the underpinning of environmental degradation in the region. Their efforts include introducing fisheries education and management, terrestrial conservation, healthcare, and women’s health services and education, agricultural training, and other efforts to increase the quality of life and understanding on how human activities impact the very resources that the local people depend on for survival. Without the buy-in of local communities, efforts to conserve this incredible region will likely be unsuccessful.

How Do I Stay Safe?

The answer to this question is a fairly straight forward product of preparation and experience with regards to the different dangers and threats I am likely to face.

Animals & Weather

As someone with a background in biology and having spent a lot of time in the African bush, I’m well aware of the animals which may be present, their habitat preferences, and behaviors. Much like traveling in bear country, simple behaviors such as keeping a clean camp, traveling only during the day, avoiding likely habitats, knowing the behaviors of species (such as predatory or territorial), and maintaining constant vigilance can go a long way.

The lakes themselves are often referred to as inland seas, where storms and large waves can be a threat. So, I will rely on my years of experience on the water and travel prepared with the right equipment: an extremely seaworthy folding sea kayak and a securely fastened PFD.

Criminal

People can also be a threat to safety, but in my experience people are generally good and welcoming, and some common sense, vigilance, and interaction with local people should keep me safe. I’ve talked with local people and asked about crime and threats to safety, and their advice is generally good. On the whole, the areas that I am visiting are mostly populated with small rural villages, which are generally extremely safe. I will have to be more vigilant around larger towns or cities, or if someone points out a specific threat.

Diseases & Injuries

The final threat to my safety on this trip is wilderness health. This poses a unique challenge on my trip because I will be traveling alone in regions that suffer from endemic tropical disease and have little or no medical infrastructure. Similarly to other threats, a combination of education, preparation, and a having a plan in place can diminish or neutralize most of these health dangers.

First, it is important to understand the diseases that pose a health threat and understand transmission, recognizing symptoms, and treatment. Prevention of infection is the single most important thing that I can do. Before I leave home, I will identify all diseases for which there is an option for immunization or prophylaxis and make sure to diligently follow through. To prevent infection from ingested diseases, I will only drink verifiably treated water and only eat thoroughly cooked or reputably packaged food. I use UV and filter treatment for water, always have the ability to boil water as a backup, and generally cook my own food.

The main routes of transmission for parasites in the region where I will be traveling include exposure to contaminated water (Schistosoma) and being bitten by insects which carry diseases (Malaria and African Sleeping Sickness). To prevent this, I will take Malaria prophylaxis, insist on wearing clothes that are treated with insect repellent chemicals, such as permethrin, use insect repellents such as Ben’s 100 DEET and Natrapel Picaridin, and attempt to keep my skin covered as well as possible. To prevent exposure to Schistosoma, I shall avoid contact with the water, especially near shore and around villages and vegetation. It is advisable to know what types of areas have a higher density of the insects, and what part of the day they are active, and avoid both if possible.

If I do fall ill or am injured, it’s important to know how to deal with it and be prepared with the necessary medicine and medical supplies to do so. I recommend taking a Wilderness First Responder (WFR) course, and doing as much research as possible into first aid and tropical disease (or whatever diseases exist in the area where you are traveling). Another excellent resource that I always bring is a small wilderness medicine book, such as A Comprehensive Guide to Wilderness & Travel Medicine by Eric Weiss, MD. I always carry a full range of medications so that I have some ability to respond to illness in the field. I am also packing a well-equipped first aid kit, in this case an Adventure Medical Kits Mountain Series Guide Kit, which has supplies to cover situations including wound care, musculoskeletal injuries, cuts, bleeding, and over the counter medications.

Emergency Evacuation Plan

Finally, I utilize a satellite telephone and medical evacuation service in case of emergency. This service provides me with a final layer of protection, should the worst happen. I can call them and speak with a doctor who can talk me through diagnosis and treatment, and if necessary, they will extract me from the field and take me to a medical facility.

So, my advice to any adventurers or people of adventurous spirit is to seize the day and go out there, but make sure to be safe by going educated and going prepared

Picture Credits: Ross Exler Photography