Check out these great tips found on REI.com

Seek Instruction

This article and accompanying videos provide an overview of 2 primary navigational tools, map and compass. But even watching and reading every word will not turn any person into a skilled backcountry navigator.

REI strongly encourages outdoor adventurers to take a course in navigation with ample field practice to build up your skills and confidence. The REI Outdoor School offers such classes in selected U.S. cities. Local outdoor and mountaineering organizations also offer similar courses. Be sure to seek one out.

Basic Tools

Map

Simple trail maps, the line-drawing variety often found in guidebooks, are useful for trip planning but NOT for navigation in the field. To safely find your way in wilderness terrain, you need the detail provided by topographic maps.

So know your maps:

Basic (planimetric) maps:

- Examples: Traditional road maps; hand-sketched trail maps provided in visitor-center handouts.

- Appearance: Flat, 2-dimensional, horizontal view of land areas showing roads, rivers and trails.

- Attributes: They display points of interest (viewpoints, trail junctions) and routes that connect them, but offer no perspective on elevation variances. Thus they may make the distance to your destination appear to be modest, but they will not indicate if a deep valley or high ridge must be crossed in order to reach it.

- Usage: OK for following a simple nature trail or making a short trip on a well-defined trail system, but insufficient for navigation should you head deep into the wilderness or step off an established path.

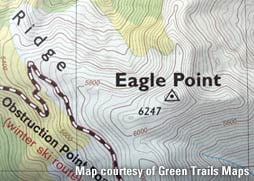

Topographic (topo) maps:

- Examples: U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) quadrangles; customized commercial and downloadable map products.

- Appearance: Areas of varying colors (or shades of gray) are overlaid with “squiggly” contour lines. Together they combine to give trained eyes a mental picture of the elevation variances in a landscape. Tightly spaced contour lines, for example, indicate steeper terrain.

- Attributes: Their ability to convey the physical relief (the highs and lows) of a landscape enables you to orient yourself in the field by identifying prominent natural features—peaks, ridgelines or valleys. They also show the location of prominent man-made features such as roads and towns.

- Usage: Always the best choice for any type of wilderness travel, from day trips to extended expeditions. Even if you’re hiking on what you believe is an established, well-signed, can’t-get-lost trail system, a topo map remains a helpful tool when you reach a viewpoint and want to identify peaks and landmarks with certainty.

Compass

Every backcountry explorer needs at least a basic compass that includes a magnetized needle floating within a liquid-filled housing. More sophisticated compasses offer useful features such as a sighting mirror or declination adjustment, but a basic compass includes all the essentials needed for navigation—magnetized needle, rotating bezel ring, orienting lines, index (degree) lines (north is 0°/360°, east is 90°, south is 180° and west is 270°) and line-of-direction (orienting) arrow.

Why not rely exclusively on a watch or GPS receiver that includes a compass? Because those are battery-reliant devices, and batteries may expire or electronic circuitry can malfunction. You need the dependability of a compass that relies only on earth’s magnetic fields.

Understanding Topo Maps

A topographic map helps you envision the appearance of terrain between 2 points. Such knowledge enables you to plan the best route of travel between them.

How Do Topo Maps Describe the Terrain?

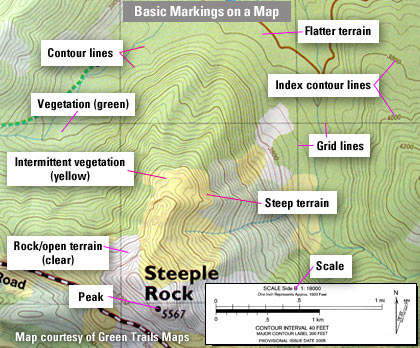

Contour lines: They connect points on the map that share the same elevation, providing a 3-dimensional perspective of the landscape. Tightly packed contour lines indicate steep terrain; widely spaced lines indicate relatively level terrain. Contour lines never intersect.

Contour interval: Contour lines are separated at specific elevation intervals. Intervals may vary by individual map, appearing every 20, 40, 80, 100 or 200 feet. But the interval used on a single map (say, 80 feet) remains consistent throughout that map. A map’s chosen contour interval is identified in the margin of each map.

Index contour lines: Every fifth contour line is the index contour line. Usually the line is slightly bolder and intermittently includes the elevation (usually the number of feet above sea level) of all points on that line.

Scale: Beyond the ratio scale (described later in this article), a map includes a horizontal graphic scale. It displays how a measurement on the map (1 inch, for example) equates to miles/kilometers of terrain covered by the map.

Colors and shading: Darker colors (or shades of gray) represent dense vegetation. Lighter colors (particularly greens) or shades of gray indicate comparatively sparse vegetation. Lighter colors (such as beige) or no colors suggest open terrain. White spaces with blue edges indicate permanent snowfields or glaciers.

Magnetic declination diagram: Printed in the margin of the map, this diagram shows the difference (declination) between magnetic north (indicated by the MN symbol) and true north (or polar north, indicated by a star symbol).

Grid: Numbers displayed around the edge of a map represent two grid systems that can be used to determine your location.

- Latitude and longitude: Exact L&L numbers are displayed in the corners of maps and at equal intervals between the corners.

- Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM): This system, used primarily by the military, divides the earth’s surface into a number of zones.

Combined, all of the above can enable you to determine your elevation, the ruggedness of the terrain around you and the most desirable route to travel to reach a destination.

Choosing a Topo Map

Two factors play a role when you evaluate maps: Scale and content.

Scale

A map’s ratio scale conveys the relationship between a measurement on the map and the distance it represents on the terrain. The most popular USGS maps offer a scale of 1:24,000, which means 1 inch (or foot, or any unit of measure) on the map represents 24,000 inches on the ground.

Mapping software makes it possible to create customized maps that offer a larger scale (say, 1:12,000 or lower) to provide greater detail. Customized commercial maps are also sometimes created at these larger scales. This is especially useful for off-trail explorers who want to choose passageways through saddles or passes that offer the least resistance.

The downside: Such maps cover a small area. People who undertake 1-way, multiday trips along a linear route often choose small-scale maps (1:50,000 or 1:62,500, for example). These maps cover a lot of land area but offer less detail. When terrain becomes very steep, contour lines runs so closely together that they appear almost as blobs rather than lines.

So if you’re a long-distance traveler, a small-scale map will give you a good overview of the territory you’re exploring (much as a road map does). The good news: You don’t have to carry a dozen or so maps to cover your trip. But if you decide to go off-trail in a certain area, all a small-scale map may offer you is a clot of tiny, tightly packed lines—likely not enough detail to make wise navigational decisions.

Note: The terms “small-scale” and “large-scale” can be confusing to beginners since ratios get smaller as their denominators get larger. Remember this: 1:24,000 is a larger scale than 1:250,000, since the fraction 1/24,000 is larger than 1/250,000.

Content

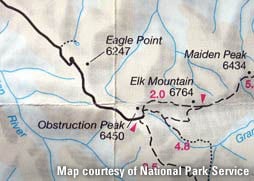

Some commercial (non-USGS) maps include additional features that can be valuable to some users. They include:

- Highlighted trails

- Elevation call-outs

- Distances between trail junctions and landmarks

- Primitive trails

- Backcountry campsites

- Springs

- Highlighted boundary lines

These additions, even GPS coordinates and personal notations, can be inserted onto maps when created using mapping software.

Map Options

USGS Quadrangles

The USGS is the major supplier of topographic maps in the United States. USGS maps cover rectangular areas of land called quadrangles. The borders of these maps are determined by latitude lines, longitude lines and the smaller divisions between them (minutes). Every square mile of the U.S. is covered by USGS maps, and each map lines up flush with the others around it.

- Pros: USGS quads are easy to find, easy to use and easy to fit together when your trail crosses over onto an adjacent map (the borders match exactly, and the titles of adjacent maps are printed on the borders of each map).

- Cons: They typically provide limited trail information. Plus their information is sometimes dated. It’s not uncommon to find that the location, even the existence, of roads, bridges, trails and shorelines have changed since the map was printed.

Commercial Maps

Private map companies sometimes enhance existing topographic maps with highlighted features or, more commonly, create customized maps that focus on popular areas that attract lots of visitation (and therefore potential customers).

- Pros: Such maps not only have key features (primarily trails) highlighted, they are updated regularly. Release dates are usually found near the scale or the magnetic declination diagram.

- Cons: Higher cost; some remote yet scenically worthwhile areas are not covered by such maps.

Mapping Software

This is an exciting, ever-evolving category of products that allows computer-savvy adventurers to create customized maps. Choose a scale that best suits your needs, insert notes and reminders, toss in GPS coordinates, print it at home on waterproof paper. Nice.

- Pros: It’s hard to beat a map customized to the exact scope of your trip.

- Cons: Higher initial cost; some degree of computer sophistication is required.

Local Maps

Many government-owned public lands (national parks, national forests, state parks, recreational areas) produce their own maps to cover the land inside their boundaries. Some are free handouts (but usually planimetric). Some handouts focus on a specific trail.

- Pros: An entire park or area is encompassed on a single map, usually with information about roads, attractions and trails. Some get regular updates.

- Cons: If they are topographic, they usually are small-scale (meaning minimal detail), and they can be expensive.

Taking Compass Bearings

A compass makes wilderness navigation possible by enabling you to accurately gauge directions from your current position to identifiable landmarks throughout the terrain that surrounds you.

The most basic function a compass provides is pointing north (magnetic north, that is). An orienteering-style compass allows you to assign a numeric value (a “bearing”) to any direction in the 360° circle around you. This means you can head toward a specific spot rather than simply ambling “south-southwest” or “due east.”

The rotating bezel of a compass is used to convert general compass directions into specific bearings. A bezel’s outer edge includes index (degree) lines that breaks down the 360° circle into 2° or 5° increments.

A bezel measures the direction towards a given object in terms of an angle—specifically, the clockwise angle between a straight line pointing due north and a straight line pointing toward the object. This bezel allows you to express any specific direction as a number between 0° and 360°.

Why is it useful to know that your campsite lies on a bearing of 40° instead of “to the northeast”? Because precise navigation results in efficiency, safety and speed.

Following a bearing off by just 1° can translate into almost 100 feet of error after 1 mile. That means that after a 5-mile hike, you could miss your target by almost 500 feet. In the wilderness, a few dozen feet can mean the difference between spotting a campsite or other landmark and missing it completely.

Transferring Bearings

On most backcountry excursions, especially those planned by beginners, compass navigation is seldom necessary. Simply following the trail carefully and checking your map from time to time should get you from campsite to campsite safely.

But if you become disoriented, or are just feeling confidently adventurous, a compass becomes a splendidly useful tool.

For example, if you know your location on the map, you can take a bearing on an unseen target elsewhere on the map and head toward that destination simply by following the bearing—even though your objective is not yet visible. Check out our video for a visual demonstration of how to transfer a bearing from map to compass:

- Identify your position and your objective on the map. Connecting those two points creates a line on the map (which you can either visualize or physically draw on the map).

- Align the edge of your compass with that line.

- Rotate the bezel so its orienting lines run parallel with the map’s orienting lines (which point to true north). This means the actual bearing have been captured at the front of the compass.

- Take the compass and turn your body until the magnetic needle lines up with the orienting arrow on the compass. At point, you will be facing the direction that will lead to your chosen objective.

You can rearrange the process and use a compass to take a bearing off a real-world object (one that is known to be on your map) and transfer that information to the map to identify your location even if you are uncertain of your whereabouts in the field. Our companion video illustrates these steps:

- Hold the compass level and aim the front of it at an object.

- Rotate the bezel until the magnetic needle is aligned with the orienting arrow of the compass.

- Locate the object on the map and place the edge of the compass on that object.

- With the edge still tight against the object, and without touching the dial, turn the entire compass until the orienting lines within the bezel line up with the orienting lines on the map.

- The edge of the compass forms a line on the map, and you now know you are somewhere along that line.

Triangulation

Triangulation is a technique that involves a map, a compass and 2 separate landmarks. It can pinpoint your position on your map even if you have no idea where you are. We demonstrate the following guidelines in our companion video:

- Pick 2 distant landmarks that you can easily identify on your map. They should be at least 60° apart.

- Take a bearing off of each object.

- Transfer those bearing to your map.

- Each bearing will form a line. Where the lines cross marks your location.

Magnetic Declination

As stated earlier in this article, the magnetized needle of a compass points toward magnetic north (abbreviated MN), but topo maps are oriented toward true north (or polar north, sometimes represented by a star symbol). Depending where you are located, the difference could be substantial—10°, 15°, 20° or more. Learn how to compensate for it by watching our video.

- Find your map’s magnetic declination diagram, usually in the margin’s lower-right corner.

- The original goal when taking a bearing is to align the magnetized needle with the orienting arrow.

- The magnetized needle must then be adjusted to the degree indicated by your map’s magnetic declination diagram. Use the index (degree) lines on the edge of the bezel.

- As you navigate, ensure that your needle is not pointed at magnetic north, but to the declination degree.